【Method】NLTK

- 0 Preface

- 1 Language Processing and Python

- 2 Accessing Text Corpora and Lexical Resources

- 3 Processing Raw Text

- 3.1 Accessing Text from the Web and from Disk

- 3.2 Strings: Text Processing at the Lowest Level

- 3.3 Text Processing with Unicode

- 3.4 Regular Expressions for Detecting Word Patterns

- 3.5 Useful Applications of Regular Expressions

- 3.6 Normalizing Text

- 3.7 0Regular Expressions for Tokenizing Text

- 3.8 Segmentation

- 3.9 Formatting: From Lists to Strings

- 3.10 Summary

- 4 Writing Structured Programs

- 5 Categorizing and Tagging Words

- 6 Learning to Classify Text

- 7 Extracting Information from Text

- 8 Analyzing Sentence Structure

- 9 Building Feature Based Grammars

- 10 Analyzing the Meaning of Sentences

- 11 Managing Linguistic Data

- 12 Afterword: The Language Challenge

0 Preface

1 Language Processing and Python

2 Accessing Text Corpora and Lexical Resources

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- What are some useful text corpora and lexical resources, and how can we access them with Python?

- Which Python constructs are most helpful for this work?

- How do we avoid repeating ourselves when writing Python code?

2.1 Accessing Text Corpora

Gutenberg Corpus

Project Gutenberg electronic text archive, which contains some 25,000 free electronic books, hosted at http://www.gutenberg.org/.

Web and Chat Text

It is important to consider less formal language as well. NLTK’s small collection of web text includes content from a Firefox discussion forum, conversations overheard in New York, the movie script of Pirates of the Carribean, personal advertisements, and wine reviews

Brown Corpus

The Brown Corpus was the first million-word electronic corpus of English, created in 1961 at Brown University. This corpus contains text from 500 sources, and the sources have been categorized by genre, such as news, editorial, and so on.

Reuters Corpus

The Reuters Corpus contains 10,788 news documents totaling 1.3 million words. The documents have been classified into 90 topics, and grouped into two sets, called “training” and “test”; thus, the text with fileid ‘test/14826’ is a document drawn from the test set.

Inaugural Address Corpus

Inaugural Address Corpus, but treated it as a single text.

Annotated Text Corpora

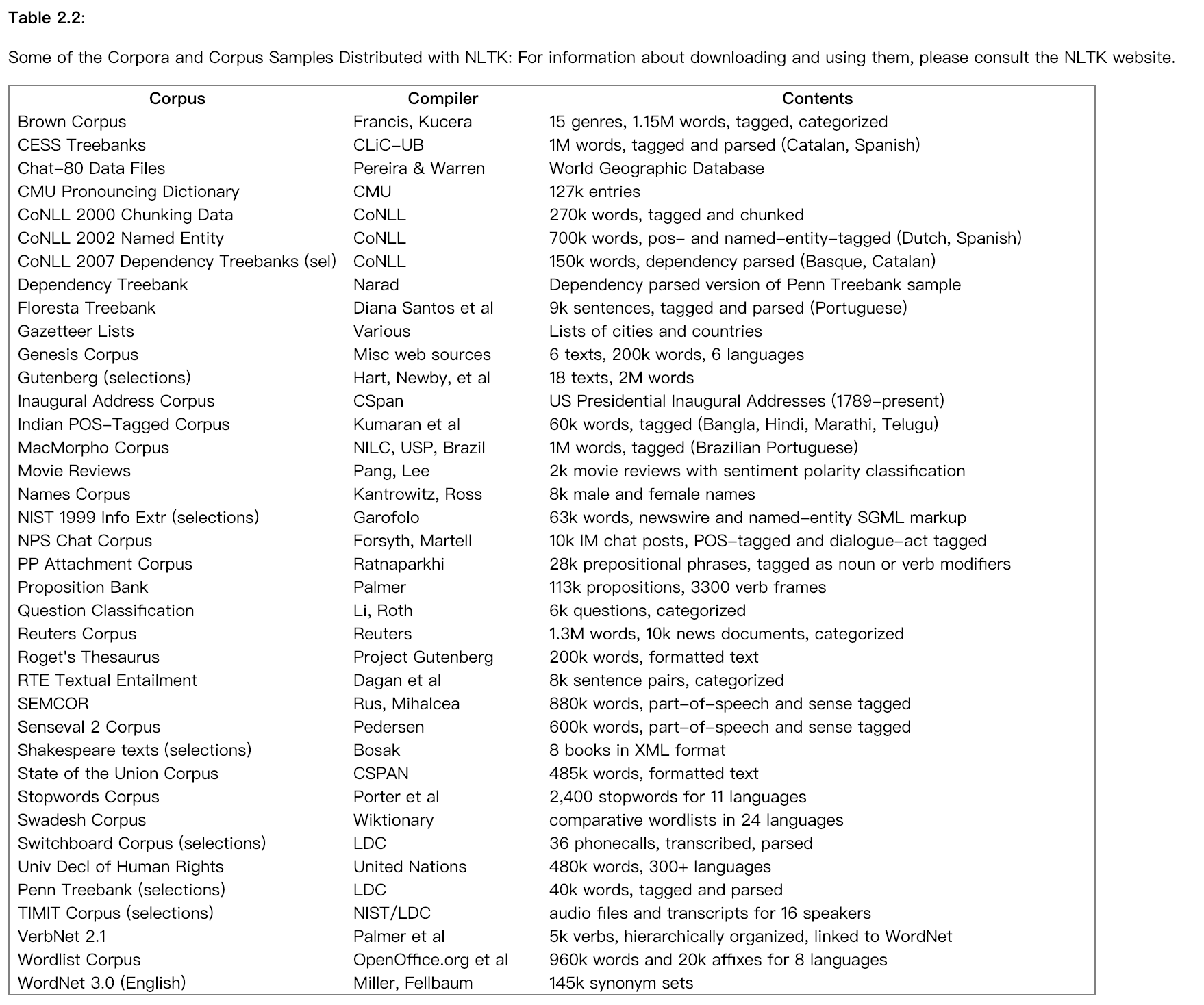

Many text corpora contain linguistic annotations, representing POS tags, named entities, syntactic structures, semantic roles, and so forth. NLTK provides convenient ways to access several of these corpora, and has data packages containing corpora and corpus samples, freely downloadable for use in teaching and research.

Corpora in Other Languages

Text Corpus Structure

Loading your own Corpus

If you have a your own collection of text files that you would like to access using the above methods, you can easily load them with the help of NLTK’s PlaintextCorpusReader.

2.2 Conditional Frequency Distributions

A conditional frequency distribution is a collection of frequency distributions, each one for a different “condition”. The condition will often be the category of the text.

Conditions and Events

A frequency distribution counts observable events, such as the appearance of words in a text. A conditional frequency distribution needs to pair each event with a condition. So instead of processing a sequence of words [1], we have to process a sequence of pairs [2]

Counting Words by Genre

Plotting and Tabulating Distributions

Generating Random Text with Bigrams

2.3 More Python: Reusing Code

2.4 Lexical Resources

A lexicon, or lexical resource, is a collection of words and/or phrases along with associated information such as part of speech and sense definitions. Lexical resources are secondary to texts, and are usually created and enriched with the help of texts.

Wordlist Corpora

NLTK includes some corpora that are nothing more than wordlists.

There is also a corpus of stopwords, that is, high-frequency words like the, to and also that we sometimes want to filter out of a document before further processing. Stopwords usually have little lexical content, and their presence in a text fails to distinguish it from other texts.

A Pronouncing Dictionary

A slightly richer kind of lexical resource is a table (or spreadsheet), containing a word plus some properties in each row. NLTK includes the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary for US English, which was designed for use by speech synthesizers.

Comparative Wordlists

Another example of a tabular lexicon is the comparative wordlist. NLTK includes so-called Swadesh wordlists, lists of about 200 common words in several languages.

Shoebox and Toolbox Lexicons

Perhaps the single most popular tool used by linguists for managing data is Toolbox, previously known as Shoebox since it replaces the field linguist’s traditional shoebox full of file cards.

2.5 WordNet

WordNet is a semantically-oriented dictionary of English, similar to a traditional thesaurus but with a richer structure. NLTK includes the English WordNet, with 155,287 words and 117,659 synonym sets. We’ll begin by looking at synonyms and how they are accessed in WordNet.

Senses and Synonyms

The WordNet Hierarchy

More Lexical Relations

Semantic Similarity

2.6 Summary

3 Processing Raw Text

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- How can we write programs to access text from local files and from the web, in order to get hold of an unlimited range of language material?

- How can we split documents up into individual words and punctuation symbols, so we can carry out the same kinds of analysis we did with text corpora in earlier chapters?

- How can we write programs to produce formatted output and save it in a file?

3.1 Accessing Text from the Web and from Disk

Electronic Books

Dealing with HTML

Processing Search Engine Results

Processing RSS Feeds

Reading Local Files

Extracting Text from PDF, MSWord and other Binary Formats

Capturing User Input

The NLP Pipeline

3.2 Strings: Text Processing at the Lowest Level

Basic Operations with Strings

Printing Strings

Accessing Individual Characters

Accessing Substrings

More operations on strings

The Difference between Lists and Strings

3.3 Text Processing with Unicode

Extracting encoded text from files

Using your local encoding in Python

3.4 Regular Expressions for Detecting Word Patterns

Using Basic Meta-Characters

Ranges and Closures

3.5 Useful Applications of Regular Expressions

Extracting Word Pieces

Doing More with Word Pieces

Finding Word Stems

Searching Tokenized Text

3.6 Normalizing Text

Stemmers

The Porter and Lancaster stemmers follow their own rules for stripping affixes. Observe that the Porter stemmer correctly handles the word lying (mapping it to lie), while the Lancaster stemmer does not.

Lemmatization

The WordNet lemmatizer only removes affixes if the resulting word is in its dictionary. This additional checking process makes the lemmatizer slower than the above stemmers. Notice that if doesn’t handle lying, but it converts women to woman.

3.7 0Regular Expressions for Tokenizing Text

Simple Approaches to Tokenization

NLTK’s Regular Expression Tokenizer

Further Issues with Tokenization

3.8 Segmentation

Tokenization is an instance of a more general problem of segmentation. In this section we will look at two other instances of this problem, which use radically different techniques to the ones we have seen so far in this chapter.

Sentence Segmentation

Word Segmentation

3.9 Formatting: From Lists to Strings

From Lists to Strings

Strings and Formats

Lining Things Up

Writing Results to a File

Text Wrapping

3.10 Summary

4 Writing Structured Programs

In this chapter we’ll address the following questions:

- How can you write well-structured, readable programs that you and others will be able to re-use easily?

- How do the fundamental building blocks work, such as loops, functions and assignment?

- What are some of the pitfalls with Python programming and how can you avoid them?

4.1 Back to the Basics

4.2 Sequences

4.3 Questions of Style

4.4 Functions: The Foundation of Structured Programming

4.5 Doing More with Functions

4.6 Program Development

4.7 Algorithm Design

4.8 A Sample of Python Libraries

4.9 Summary

5 Categorizing and Tagging Words

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- What are lexical categories and how are they used in natural language processing?

- What is a good Python data structure for storing words and their categories?

- How can we automatically tag each word of a text with its word class?

5.1 Using a Tagger

5.2 Tagged Corpora

Representing Tagged Tokens

Reading Tagged Corpora

A Simplified Part-of-Speech Tagset

Nouns

Verbs

Adjectives and Adverbs

Unsimplified Tags

Exploring Tagged Corpora

5.3 Mapping Words to Properties Using Python Dictionaries

Indexing Lists vs Dictionaries

Dictionaries in Python

Defining Dictionaries

Default Dictionaries

Incrementally Updating a Dictionary

Complex Keys and Values

Inverting a Dictionary

5.4 Automatic Tagging

The Default Tagger

The Regular Expression Tagger

The Lookup Tagger

Evaluation

5.5 N-Gram Tagging

Unigram Tagging

Separating the Training and Testing Data

General N-Gram Tagging

Combining Taggers

Tagging Unknown Words

Storing Taggers

Performance Limitations

5.6 Transformation-Based Tagging

5.7 How to Determine the Category of a Word

Morphological Clues

Syntactic Clues

Semantic Clues

New Words

Morphology in Part of Speech Tagsets

5.8 Summary

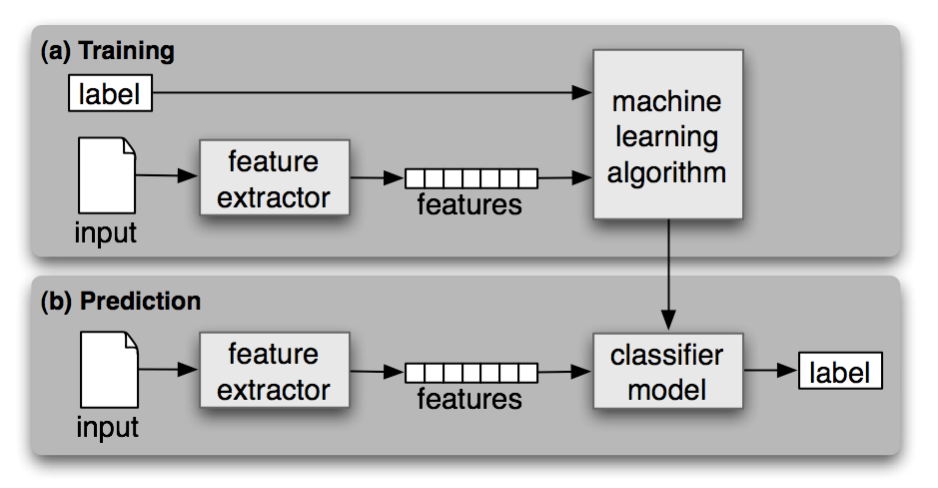

6 Learning to Classify Text

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- How can we identify particular features of language data that are salient for classifying it?

- How can we construct models of language that can be used to perform language processing tasks automatically?

- What can we learn about language from these models?

6.1 Supervised Classification

Gender Identification

Choosing The Right Features

Document Classification

Part-of-Speech Tagging

Exploiting Context

Sequence Classification

Other Methods for Sequence Classification

6.2 Further Examples of Supervised Classification

Sentence Segmentation

Identifying Dialogue Act Types

Recognizing Textual Entailment

Scaling Up to Large Datasets

6.3 Evaluation

The Test Set

Accuracy

Precision and Recall

Confusion Matrices

Cross-Validation

6.4 Decision Trees

Entropy and Information Gain

6.5 Naive Bayes Classifiers

Underlying Probabilistic Model

Zero Counts and Smoothing

Non-Binary Features

The Naivete of Independence

The Cause of Double-Counting

6.6 Maximum Entropy Classifiers

The Maximum Entropy Model

Maximizing Entropy

Generative vs Conditional Classifiers

6.7 Modeling Linguistic Patterns

What do models tell us?

6.8 Summary

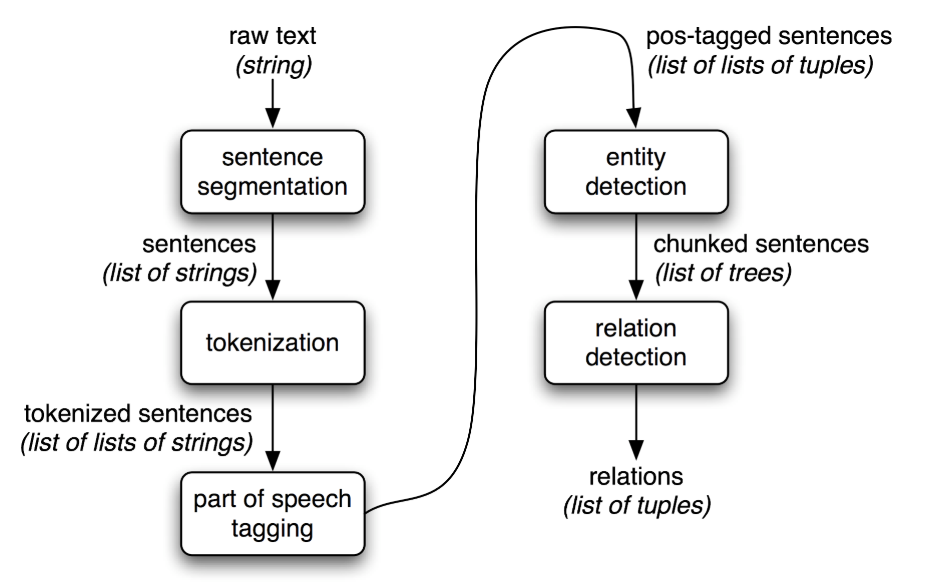

7 Extracting Information from Text

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- How can we build a system that extracts structured data, such as tables, from unstructured text?

- What are some robust methods for identifying the entities and relationships described in a text?

- Which corpora are appropriate for this work, and how do we use them for training and evaluating our models?

7.1 Information Extraction

Information Extraction Architecture

7.2 Chunking

The basic technique we will use for entity detection is chunking, which segments and labels multi-token sequences as illustrated in 7.2. The smaller boxes show the word-level tokenization and part-of-speech tagging, while the large boxes show higher-level chunking.

Noun Phrase Chunking

Tag Patterns

Chunking with Regular Expressions

Exploring Text Corpora

Chinking

We can define a chink to be a sequence of tokens that is not included in a chunk.

Representing Chunks: Tags vs Trees

7.3 Developing and Evaluating Chunkers

Reading IOB Format and the CoNLL 2000 Corpus

Simple Evaluation and Baselines

Training Classifier-Based Chunkers

7.4 Recursion in Linguistic Structure

Building Nested Structure with Cascaded Chunkers

Trees

Tree Traversal

7.5 Named Entity Recognition

7.6 Relation Extraction

7.7 Summary

8 Analyzing Sentence Structure

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- How can we use a formal grammar to describe the structure of an unlimited set of sentences?

- How do we represent the structure of sentences using syntax trees?

- How do parsers analyze a sentence and automatically build a syntax tree?

8.1 Some Grammatical Dilemmas

Linguistic Data and Unlimited Possibilities

Ubiquitous Ambiguity

8.2 What’s the Use of Syntax?

Beyond n-grams

8.3 Context Free Grammar

A Simple Grammar

Writing Your Own Grammars

Recursion in Syntactic Structure

8.4 Parsing With Context Free Grammar

Recursive Descent Parsing

Shift-Reduce Parsing

The Left-Corner Parser

Well-Formed Substring Tables

8.5 Dependencies and Dependency Grammar

Valency and the Lexicon

Scaling Up

8.6 Grammar Development

Treebanks and Grammars

Pernicious Ambiguity

Weighted Grammar

8.7 Summary

9 Building Feature Based Grammars

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- How can we extend the framework of context free grammars with features so as to gain more fine-grained control over grammatical categories and productions?

- What are the main formal properties of feature structures and how do we use them computationally?

- What kinds of linguistic patterns and grammatical constructions can we now capture with feature based grammars?

9.1 Grammatical Features

Syntactic Agreement

Using Attributes and Constraints

Terminology

9.2 Processing Feature Structures

Subsumption and Unification

9.3 Extending a Feature based Grammar

Subcategorization

Heads Revisited

Auxiliary Verbs and Inversion

Unbounded Dependency Constructions

Case and Gender in German

9.4 Summary

10 Analyzing the Meaning of Sentences

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- How can we represent natural language meaning so that a computer can process these representations?

- How can we associate meaning representations with an unlimited set of sentences?

- How can we use programs that connect the meaning representations of sentences to stores of knowledge?

10.1 Natural Language Understanding

Querying a Database

Natural Language, Semantics and Logic

10.2 Propositional Logic

10.3 First-Order Logic

Syntax

First Order Theorem Proving

Summarizing the Language of First Order Logic

Truth in Model

Individual Variables and Assignments

Quantification

Quantifier Scope Ambiguity

Model Building

10.4 The Semantics of English Sentences

Compositional Semantics in Feature-Based Grammar

The λ-Calculus

Quantified NPs

Transitive Verbs

Quantifier Ambiguity Revisited

10.5 Discourse Semantics

Discourse Representation Theory

Discourse Processing

10.6 Summary

11 Managing Linguistic Data

The goal of this chapter is to answer the following questions:

- How do we design a new language resource and ensure that its coverage, balance, and documentation support a wide range of uses?

- When existing data is in the wrong format for some analysis tool, how can we convert it to a suitable format?

- What is a good way to document the existence of a resource we have created so that others can easily find it?